Earth

Alex Eaton: Let’s Talk About Poop (Animal Manure, That Is!)

Alex Eaton, CEO and cofounder of Sistema Biobolsa(or Sistema.bio), talks about the innovative solution Sistema.bio presents to small (and even larger-scale!) farmers. This incredible biodigester system turns animal manure into both rich fertilizer and methane gas that can be used for fuel and heat. In this way, Alex and his team are addressing climate change, food insecurity, and poverty around the world by providing the full package: technology, training and financing of a sustainable waste-to-resources infrastructure that truly works for small farmers.

Tune in to hear about:

- How this magical biodigester works. (Of course it’s not magic, but it’s really, really cool science.)

- The way Sistema.bio gives small farmers a game-changing new tool—plus the financing and education that must come with it for this change to be attainable.

- Exactly how reliant our world is on small farmers—especially in places like Mexico where Sistema.bio is based.

- Why Alex applauds vegetarian and vegan diets but doesn’t think eating that way is the ONLY way to be a good steward of our earth.

- The similarities between soil and bank accounts (think long-term investments).

Listen at the link above, on iTunes, Stitcher, Google Play or wherever you get your podcasts.

Transcript: Rootstock Radio Interview with Alex Eaton

Air Date: January 21, 2019

Welcome to Rootstock Radio. Join us as host Theresa Marquez talks to leaders from the Good Food movement about food, farming, and our global future. Rootstock Radio—propagating a healthy planet. Now, here’s host Theresa Marquez.

THERESA MARQUEZ: Hello, and welcome to Rootstock Radio. I’m Theresa Marquez and I’m here with Alex Eaton, who is the CEO and co-founder of the Mexico City–based company Sistema.bio, a social business addressing climate change, food security, and poverty around the world by providing technology development, training, and financing of sustainable waste-to-resources infrastructure for small farmers. Alex is an Ashoka Fellow and a Switzer environmental leadership fellow, who holds a degree in journalism and environmental engineering. Welcome, Alex.

ALEX EATON: Hi, how are you doing?

TM: We’re doing great. And I understand that you are on the side of the road in Puebla, Mexico. So that’s kind of exciting. And I’m excited to talk with you about the technology that you’ve been developing there. Let’s get right to it: What is Sistema.bio?

AE: So, Sistema.bio fundamentally is a strategy to allow small farmers to be more efficient by combining technology, training, and financing. So, really what we try to do is to come up with a core set of technologies that we feel really improve the efficiency and productivity of farmers, make sure that they’re trained in this technology and that we can provide the resources to [do?] inclusive financing to make sure that they can make that investment in their farm.

And so I would say what we’re trying to do is build a bit of a movement around the small farmer. It’s really a massive group of people around the world, probably two billion people living on small farms today. And they just systematically don’t have access to technology that’s built for them, training that really takes them to their specific context, and most of all access to inclusive financing.

TM: Well, wow, that’s the triple whammy that’s needed there. And so it sounds to me that you’re not only working on helping to improve the livelihood of those two billion small farmers. You’re really helping to improve the whole social justice part of our world today. When we talk about the small farmers, am I correct, it’s mostly small farmers who are working with livestock? And we’re not talking about several thousand in a CAFO, we’re talking maybe six or twelve on a farm. Am I getting that right?

AE: Yeah, that’s exactly right. About 65 percent of our clients today have less than ten animals. They’re working on less than five hectares—sort of less than 10 acres of land. And what we’re really trying to do is just help them more efficiently use their resources. Which, by the way, is really the largest group of farmers in the world. So 80 percent of the global food supply is produced by people on these really, really small plots of land who have been characterized, I think, as very inefficient because of the systemic lack of technology and training.

But it doesn’t really have to be that way. The idea that bigger is better, that CAFOs and this industrial farming practice is really the best strategy to feed the planet is something that I’ve been able to see very clearly isn’t true. It’s just that the small farming community needs better access to markets and they need better technology to become a bit more efficient. But on a per hectare basis, small farms that are doing more intercropping and more robust and versatile farming practices can really actually produce a lot more per hectare than a lot of these industrial alternatives.

TM: That’s exciting to hear. And it makes such common sense to me. Can we back up just a little bit, Alex? Sistema.bio—you’re a CEO and co-founder. What brought you to that idea?

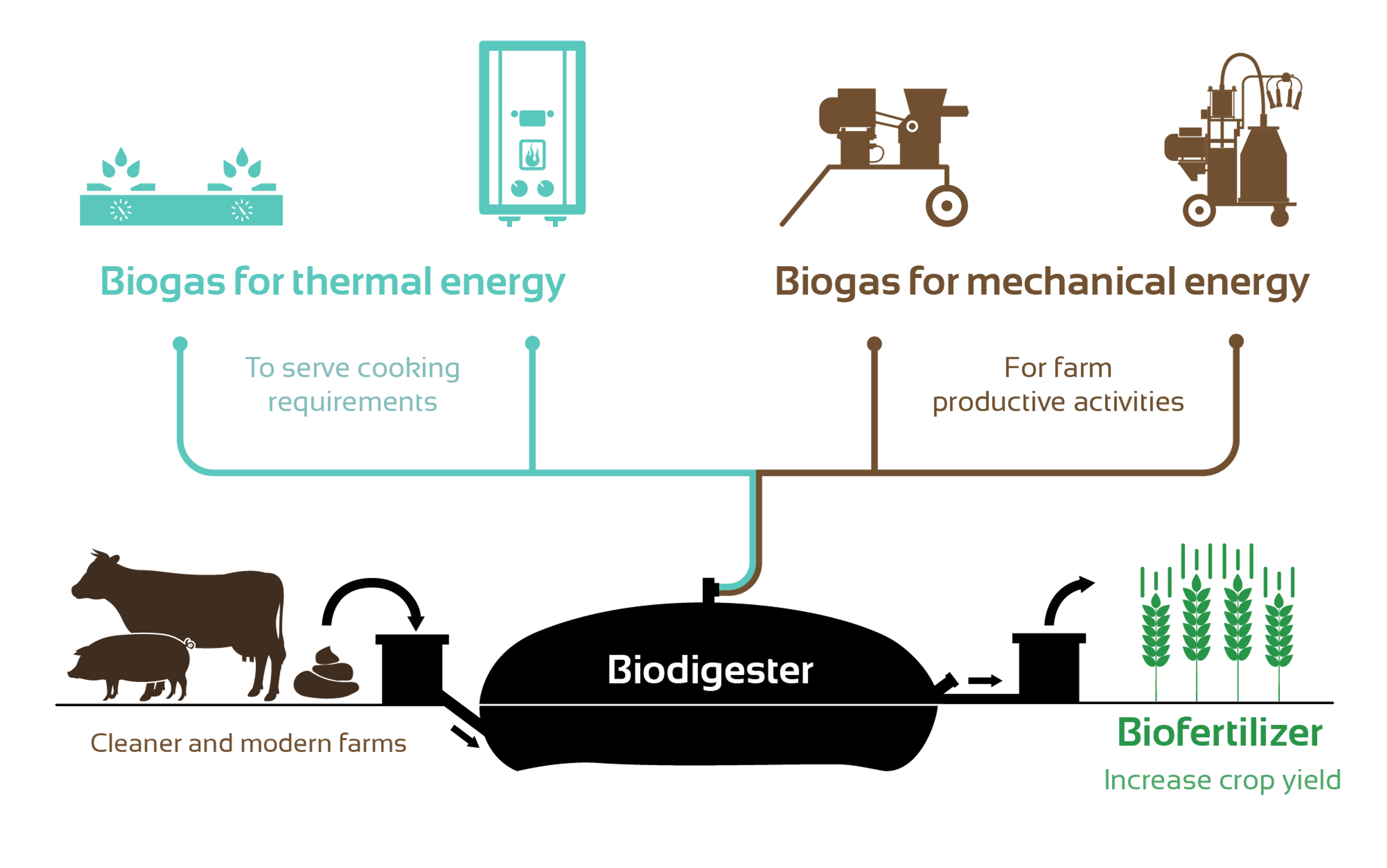

AE: So, our core technology basically takes animal manure and it provides an environment in a closed container so that animal manure breaks down the bacteria and creates a natural gas that we then capture and we can pipe to different gas uses—like cooking or heating, agricultural processing [unclear]. And in that process, what we’ve done is liberate all the nutrients that was in that manure so that it’s now plant-available. The pathogens have been 99 percent eliminated. We’ve basically converted a lot of the volatile solids into gas, and that leaves a very stable and high-nutrient value liquid fertilizer that farmers can use to displace chemicals.

So this idea isn’t one [unclear—that’s more?] that I necessarily came up with. I grew up on a small farm, so it was just always very clear the need for resource efficiency, the connection that energy and agricultural input have with the sustainability of the farm. And so I actually started working in solar power with rural communities over 15 years ago. And what I realized is that the problems that they were facing on energy weren’t disconnected from the other issues that they had.

And so when I first learned about biogas technology, it was because I saw a homemade bio digester, which is what we manufacture today, and it was very functional but it was really ugly. It smelled really bad and was not easy to use. And we were selling these new, sort of, solar kits that were quite efficient and beautiful and easy to install. So I really got to thinking why there wasn’t a more turnkey package for biogas technology that had so many more benefits than just the energy for small farmers. We were only this homemade design at the time.

So the whole idea sort of started as a challenge to create a prototype that would be reliable and functional for small farmers. And then the project really grew from there, because once you have a prototype you start up wondering what your distribution model is, how do you get it into people’s hands, and then how to make sure that they’re trained properly. And then we eventually ran up against the inevitable issue of how do people finance these things if they’re paying in average of 100 percent interest rate in agricultural markets in some places around the world? So we developed an in-house financing mechanism as well. So the whole process has been just an iteration of [unclear], from one of the problems that [unclear] farmers have, and building products and models around this.

(7:57)

TM: It’s really quite exciting to think about it. So, for our listeners, just to kind of recap so that it’s truly understandable, what Alex and his colleagues are doing is they’re going to some of these small farmers, of which two billion small farmers around the world today, and they’re basically showing them that they can capture the manure, the wastes, from their animals and put it into a system that encloses it, and then they capture the gas. And is that methane gas, Alex?

AE: It is. It’s methane gas—it’s very similar to natural gas but [unclear] it’s slightly less pure.

TM: So it’s the dreaded methane gas that creates global warming that we’d like to try and reduce that. It then can be used, for example, to fuel a cookstove. And then what’s left over is great fertilizer for those farmers to use on their farm. So you might say, it’s like got just tremendous commonsense, total use of something that ordinarily we would consider a waste. Although farmers, of course, never see manure as a waste.

So, Alex, this idea of the methane, does it still get released as it’s cooked? Or is that in a different form by the time it goes through a cook stove?

AE: The key with methane is to destroy it. So the best way to destroy methane is to burn it. And then what you’re left over with is CO2. What’s interesting about the CO2 cycle within agriculture is that the CO2 itself is actually in balance. So the plants grow and they pull CO2 out of the atmosphere, it’s eaten by a cow. As that goes through the process, that CO2 is then bound with agriculture. What happens, the danger of methane and why methane is such an important greenhouse gas is that if methane itself released it can capture 25 times more heat than just a molecule of CO2.

And so when you burn the methane, it breaks down into water and CO2, basically. And that CO2, again, is in balance with the carbon cycle. So the key for us—and actually this project really, kind of, evolved as a greenhouse gas project. So what’s really interesting about biogas at small farms is that all of their manure today is producing methane that goes just straight into the atmosphere. So the first step is to capture that methane. And when you destroy that methane, you’re essentially providing useful renewable energy. We run engines on that, we can create electricity, we can use it to connect to the grid, we can distribute that gas. It’s a very, very versatile renewable energy source.

But then we also displace the other fossil fuels or biomass fuel that they would’ve used if they didn’t have access to that gas. So that’s the double—

TM: That’s right!

AE: —greenhouse gas savings. And then there’s a third savings, which is the chemical fertilizer displacement as well. And every kilo of chemical fertilizer produces 1.4 to 1.8 kilos of the CO2 emissions from the production, transport, and distribution and then off-gassing that happens in the field. So it really sort of has this triple reduction that really helps farmers go from one of traditional… I mean they’re not super high-impact, but…. [unclear] and ones that are really all of a sudden driving renewable energy and totally in cycle with natural agriculture carbon cycles. So that’s what’s kind of so exciting.

Unfortunately, what happened is that the price for a ton of carbon kind of crashed very early in the project. And so, instead of being able to really leverage that as a source of income, we’ve really had to focus on how to make this product viable in an agricultural market. Which I think has ultimately has made it stronger as a company, because we’ve really had to focus on ensuring that farmers want to buy [unclear—deeds?] and want to buy lots of them, and that it provides a high level of return on investment. So then, sort of excluding the carbon. So the carbon is kind of this cherry on top that we have, and we’re starting to work through new strategies to commercialize that as well, which just allows us to reach more farmers.

TM: Well, it just seems so exciting to think that you can be a small farmer, you can have a few animals; then the biodigester then works to both create fertilizer as well as energy for heat and for gas, which then, the farmers must save from not having to find other gas or wood or use other wood or other things to both use to cook and also to heat. So it seems such like a commonsense, practical thing. A couple questions though: How about the biodigesters? Are they very expensive to put in?

AE: So our product line is actually pretty interesting, because we can serve everywhere from two cows to 200 cows. Our smallest digester costs about $600. So it’s quite accessible and we offer about a year payment plan for that, so farmers are able to pay less than $50 a month, which makes it quite accessible at the smallest scale.

But we also have systems that are quite a bit more advanced, that run electrical generators, that supply into the grid, that are more automated in terms of the waste management. And it uses the same sort of fundamental platform or fundamental reactor, but then it just sort of depends on the size of those reactors and the bells and whistles we add. So we basically sell systems between about $600 and $60,000. But obviously the systems that are more expensive are going to slightly larger farmers that can also afford that.

What you commented on earlier, and I think it’s really important to mention, is the social justice element of this. We see the world in which we kind of have three massive threats to humanity that we’re facing, and that’s poverty, food security, and climate change. And obviously there’s many more, but sitting kind of at that nexus is the small farmer. Of the two billion people that live on small farms, about a billion are the poorest people on Earth. And they’re sitting right at this really important cross section of food security. And we’ll need their farmland to produce more food.

And the question is: Will we do that in a Green Revolution kind of way where we’ll just throw chemical fertilizer at it? Or will we really [unclear] not only contaminates the land but it leaves these farmers in this high-input scenario when their margins are so low that they’re stuck in the cycle of poverty, even if they’re able to grow. But our vision for the future is that all of those farmers [unclear] can produce more of the things that they need on their own farms, so recycling their nutrients, creating the energy that they need to operate on their farms, and that allows them to increase their margins.

So if you could increase food production, reduce greenhouse gases, and reduce poverty, and then in that same, that cross section of the small farmer [unclear], and we could do that at scale, that’s when it really starts getting exciting for us.

TM: That is very exciting. And this is all linked to helping get smaller farmers who are in poverty more resources, more efficiencies. One of the interesting things is, we have, in the United States—and I know you’re down in Mexico right now—but we have the demonization of livestock. And sometimes I almost feel like it’s a First World problem. There’s 1.3 billion people probably having some livestock and actually hugely dependent on it. I mean, isn’t livestock a critical part of helping really poor people feed themselves and stay solvent in some way or another?

AE: Yeah, it’s funny you bring this up, because I obviously have friends that are environmentalists that have been very critical of, sort of, “If you actually cared about the environment, you would be just trying to get all these farmers to sell all their animals and turn into vegetarians,” and stuff. Which, I get that point, but I think you’re right-on, that this is a bit of—I wouldn’t call it a First World problem because some of the biggest, most horrendous CAFOs I’ve every seen in my life are here in Mexico and in other parts of the world.

What I would say is that poison is about dose, right? So you probably could get rid of all of those CAFOs and all of that inefficient grazing, and a ton of the livestock practices that are really damaging. But I think that, honestly, one of our best environmental and climate hopes—and in some ways, kind of our humanity is tied into this—is just to make sure that people that are vegetarian, all those vegans, are gonna respect it. You have this future in which the animal could be put back into its normal cycle in the ecosystem, which is actually building soils, helping break down all that cellulotic matter that turns photosynthesis into actual nutrients and be able to drive that back into the soil. And if we do that right, we can really make a beautiful, well-balanced diet, [a] beautiful, well-balanced agricultural system that supports the soil, supports good treatment of animals.

And I really feel like small farmers are the ones that are in the best position to do that, because what I see is that the animal conditions of these smaller farms, you just really can’t compare them to these larger systems that you see. When a farmer has six or seven cows, we’re back in the situation where all these cows have names, they’re very well-treated. And the realities of them being working animals still remains, but their integration into the overall ecosystem and the little adjustments we can make in that farming practice to make it much more sustainable is really quite exciting. I mean, all of the work on sustainable grazing—we work with a lot of low-grazing systems where if we’re recycling the nutrients back into the soil, and then we’re cutting very efficient grasses and forages, then we really reduce the amount of land that each animal’s taking up, we can really focus on animal health, and we can really focus on soil health.

I just think people that are vegetarian or vegan today are totally right on and totally well-intentioned, but I don’t think it’s fair to blame the animal. It’s really the systems that they’re being raised in. So we see a massive difference. Our dairy farmers have nothing in common with 10,000-head dairies, and similar league with the small pig farms and things like that. They’re just really not the same thing, and scale is what really contributes to that.

So that’s why we feel really strongly about working with small farmers. We really feel like we can have a much more rational, ecological, and well-balanced diet. We need meat, and I think that there’s a way to do that in balance with the ecosystem. But it takes a lot of work. The work that you guys are doing, promoting organic in the U.S. and promoting small farmers, it needs to come on every single level. And a lot of that is kind of consumer and diet-based thinking.

TM: “Meat on the side,” we like to say.

AE: Right.

(20:32)

TM: Well, if you’re just joining us, you’re listening to Rootstock Radio and I’m Theresa Marquez. And I’m so honored today to be talking with Alex Eaton, who is CEO and co-founder of the Mexico City–based company Sistema.bio, a social business addressing climate change, food security, and poverty around the world.

It’s so exciting what you’re doing here. And we were talking about how so many of these small farmers really depend on their seven or ten or twelve animals for a living, for their sustenance. And it’s a lot different-looking farm system than the kinds of animal-concentration, CAFO feedlots that we’re kind of familiar with in the U.S.

And you were talking about how you want to respect vegetarians and vegans, and so do I. But I keep having to ask this question: If we don’t have animal manures as fertilizer, what will we use to fertilize those lovely, beautiful vegetables that our vegetarian and vegan friends like to eat?

AE: Yeah, just to give you a bit of a scale, we’ve done about 16 years, we have about 50,000 hectares under management using our fertilizer system. And what I can say is, just so you can have a sense, our smallest system—so the very, very small system that just receives the waste from two to four cows—produces enough organic fertilizer to displace about 80 to 90 percent, depending on a number of different factors around soil and other things, but 80-90 percent of the traditional recommended chemical fertilizer [unclear—doses].

So, similarly to many other things, I’m not [unclear] against nitrogen fertilizer by any means—it certainly was an amazing advancement and probably helped us not have our food systems collapse up to this point. But I think we need to really rationalize that on how we move forward. So I think, in a perfect world, we could leverage a little bit of that science and reduce the vast majority of it.

So if you multiply that out, well-managed with all the manure from a farm, five or six cows able to fertilizer three to five hectares of different crops is really phenomenal. And that is our best hope to reduce chemical fertilizer consumption, which is really an energy problem also. It takes a ton of energy to pull that nitrogen out of the air in the way that they do it, and it’s also very damaging to soils and a number of other things. And so, the other [unclear—track is] farmers are needing more and more nitrogen [unclear—incorporated] each year as their soil [unclear—loses] the biology to break [unclear] and transform that nitrogen naturally.

So, this sort of soil question, even though we’re kind of [unclear] very much about waste and energy, the soil question is building soil health, and this is fundamental both from the climate change point of view but also the social justice point of view. Farmers have very small plots of land. And so when they’re given chemical fertilizers [unclear—it alters] the natural capital that is built up in that soil with the organics, the biology. In an organic system that just is getting better and richer every single year. But when we start using chemical fertilizers, you essentially just extract from those nutrients—kind of more like pulling out of a bank account rather than investing.

So we really see that rationalized within a sustainable agricultural system as well as sort of thinking of the soil very much as a bit of the actual capital that these farmers are able to build.

TM: I love that, Alex. I love the idea of seeing soil as this investment, just like a bank account. And also, speaking of bank accounts, when you can use these by-products, not only are you getting gas to fuel your stove or your heater and you’re getting fertilizer, well, you don’t have to pay for those expensive inputs. Even nitrogen is very expensive. And we certainly know that these small farmers need to save wherever they can.

AE: Really, our sort of core measure is how long it takes a farmer to pay back his investment with the savings that he has, and we’re really strict about how we measure that. And our average globally, it’s just over a year, but some dairy farmers in Central Kenya can pay back their system in 10, 11 months, just based on the prices that they’re paying for fertilizer and energy today. So this is definitely, first and foremost in how we go to market is really with just a really good investment, a really quick payback. And then we finance that kind of payback period so that they can be as cash-flow-positive or as close to it as possible during the course of their repayment.

It’s a really good economic deal and [unclear] piggybacking all these ecological and social benefits on top of that.

(26:04)

TM: Well, that is so exciting, to know that they can actually pay that back in a year. But, you know, I’m looking that you have another aspect. You talk about the economics, you talk about the biodigester, the actual technical stuff. Then you also have the Bio Escuela—and escuela, as many of you probably know, is the Spanish word for “school.” That also is part of it too: you have to get out and teach the farmers, the small farmers and those involved in it. What is that like? How long does it take to really get through a course and really understand how to work this system?

AE: So education is a big part of what we do. And so there’s kind of two fundamental areas. The first is just the training that goes along with the, sort of, sales process and the installation and the adoption process that we have with each farmer. So there, we really see these kind of customized, small, very specific training courses so people understand how to use their digester, optimize the output. And then we communicate via SMS and other different communication medias to try an reinforce that and follow up with them over time with a pretty strict visitation cycle that we have with all the farmers to make sure that they’re always getting the most out of their systems.

And there’s something really powerful about the idea that you can turn manure into resources. Like manure, by definition—I’m trying really hard to not use a word that makes a bleep or anything—but it is waste, right? It’s something that doesn’t… So being able to create value that is actually this really interesting frame shift that allows people to kind of see the world a little bit different. Sort of, “Wow, if they can turn the grossest thing into something beautiful, then what other transformational opportunities are there?” And that’s what’s been really fun about working with small farmers, is you just have so many creative, unique individual and agricultural systems that it’s this unbelievable laboratory of [unclear] of learning and sharing. And that’s what we’re really trying to be a part of.

TM: Well, Alex, I am inspired by what you’re doing, and I’m so happy about what you’re doing too. Www.Sistema.bio. So, Alex, I can’t thank you enough for this great work that you’re doing. And thank you so much for taking the time to talk with us today and inspiring us.

AE: Yeah, thank you guys for the work you’re doing, and thanks for giving me an opportunity to share with your listeners.

You can listen to Rootstock Radio on the go wherever you get your podcasts, and find us online at RootstockRadio.com. Rootstock Radio is brought to you by Organic Valley.

© CROPP Cooperative 2018

Related Articles

- Tags:

- climate,

- innovation,

- social justice,

- renewable energy,

- Rootstock Radio