Earth

Dr. John Fagan on the Toxins in our Food and Environment

Today on Rootstock Radio, we’re talking to Dr. John Fagan, CEO at the Health Research Institute Laboratories in Iowa and Executive Director at the Earth Open Source Institute. John is a researcher, a respected authority on food and agriculture sustainability and passionate about issues from climate change to keeping toxins out of our food.

Today’s episode also marks the end of an era for this 4-year project: This is the final episode of Rootstock Radio. To the 40 community radio stations across the country who air our show and the countless podcast listeners who download it around the world: Thank you for supporting us and celebrating so many Good Food Movement changemakers with us.

So for one last time…

Tune in to hear about:

- How Health Research Institute Laboratories works on an all-encompassing model of health: promoting healthy soil, healthy crops, healthy food and a healthy planet

- Why John believes that climate change is really about us. (Mother Mature can take care of herself.)

- The guy behind the research for the study Kendra Klein talked about on her recent Rootstock Radio episode (hint, it’s John!)

- The difference between organic and conventional food, on a scientific level.

- How YOU can contribute to a crowd-sourced glyphosate environmental research study.

Listen at the link below, on iTunes, Stitcher, Google Play, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Transcript: Rootstock Radio Interview with Dr. John Fagan

Air date: June 17, 2019

Welcome to Rootstock Radio. Join us as host Theresa Marquez talks to leaders from the Good Food movement about food, farming, and our global future. Rootstock Radio—propagating a healthy planet. Now, here’s host Theresa Marquez.

THERESA MARQUEZ: Hello, and welcome to Rootstock Radio. I’m Theresa Marquez, and I’m here today with John Fagan, who is the CEO at Health Research Institute Laboratories in Iowa, and he’s the executive director at the Earth Open Source Institute. John is very well known as an authority on food and ag sustainability, and besides being an authority you can tell he’s a researcher, so lots to learn from him today. Welcome, John.

JOHN FAGAN: Oh, it’s great to be with you today, Theresa. Thank you so much.

TM: Well, I think the first thing is, what is the Health Research Institute?

JF: Well, health is a word that covers a broad range. And HRI, Health Research Institute, actually manages to cover that whole range as well. We have healthy soil, we have healthy crops, and healthy food, and healthy planet. And that’s what we’re about.

Essentially, you could put it this way. For me, right now, the big concerns are two: one is soil quality and the other is the climate. And in the soil area, the FAO tells us, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, tell us that we have, as a species, we have less than sixty harvests left. Our soil has become so degraded, and is continuing to degrade, that if we don’t change what we’re doing in terms of agriculture, there won’t be enough soil left to feed humanity. We’re coming up on that. Sixty years is not a long time when you’re talking about soil.

And then the other is climate change. And we maybe have another few years, if we can take action, we can actually sort of come out of this without losing the niche for humanity, because that’s what climate change is. That’s really, that’s what climate change is all about, or what our concerns are all about, is that it isn’t saving the planet or taking care of Mother Nature. Mother Nature has done pretty well over the last [unclear]—

TM: She doesn’t need our help, eh?

JF: Right, yeah. Now, but it’s quite conceivable that we could essentially create a situation where the niche for human beings goes away, but life will continue. It will just be different forms, and they will come back. It may take a very long time, but there will be a whole new phase of things that way.

So I’m up for doing what we can to restore and at least protect humanity’s niche. So taking care of healthy soil so that we… And remember, healthy soil means it’s going to produce good food, but it’s also going to sequester carbon, and that carbon sequestration is drawing down the problem for climate change. It’s great to conserve our use of fossil fuels, but that’s not going to save us. That’s not going to fix the problem. We have to actually reverse the direction that the carbon is going or we’ll never get out of this.

And in fact, I heard a scary statistic the other day. They talk about four degrees of warming. The reality is that because of the nature of the heat sink, nature of things like the ocean, with the change in climate that is here today, there will be increases in temperature for…it will not stabilize for about a thousand years. And it will actually—this is science, okay—and it will actually result in much more than four degrees, unless we do something to reverse it. And that’s what I’m up for, and I feel that we all need to get involved with that.

But our goal is to make that easy for people. I’ve described the problem. Our strategy for solving those problems, or addressing those problems, or contributing to the solution to those problems, is through agriculture: that if we can get farmers to farm in a way that brings carbon back into the soil and thereby creates healthier soil and sequesters carbon, if we get that to happen, it will correct both of those situations at once—both the risk of no longer being able to grow enough food for everybody and the impending risk of more serious climate change than what we’re experiencing today.

And our strategy for doing that is to make use of people’s appreciation for pure, safe, healthy food. The challenge is this, though: that a hydroponic tomato doesn’t look that different from a tomato that’s been grown in rich, organic soil, but in terms of nutrition they’re very different.

TM: And they taste different!

JF: They do, they taste different. And what we can do, though, and this is what we’re doing, is we’re looking at both the bad guys and the good guys. We’re looking at the toxins and the contaminants that may be present in foods, and also looking at the nutrition of those foods. And we use very powerful technology for that called ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography linked to mass spectroscopy [spectrometry?].

TM: Goodness!

JF: Yeah, it’s a mouthful! And these techniques are capable of detecting literally parts per billion—in fact, parts per trillion—of pesticides, and to measure those in foods. And this method is also capable of, we can take a single sample of food, grind it up, extract it, and then in that one sample there’s probably, depending on the food, if it’s a complex plant, a vegetable or something like that, there may be as many as a thousand different compounds in there, different molecular species. And with this technology we can separate all of those and then measure the levels of each of those. And we compare the levels of all thousand of those for the organically grown tomato and the hydroponic tomato. And from that, we can actually identify which nutrients are present in one and not in the other, and tell someone, “Well, you know, if you eat this tomato it’s going to fulfill such-and-such amount of your daily needs for this vitamin and this nutrient and this antioxidant,” and on like that.

TM: John, just to back up just a little bit: so the Health Research Institute is doing laboratory work and testing, not only of the different kinds of food and comparing them, different kinds of food the way it was grown, but don’t you also look at soil? And you’re looking at the food for its nutritional benefits, but are you also doing any testing? I know that you do glyphosate testing with humans.

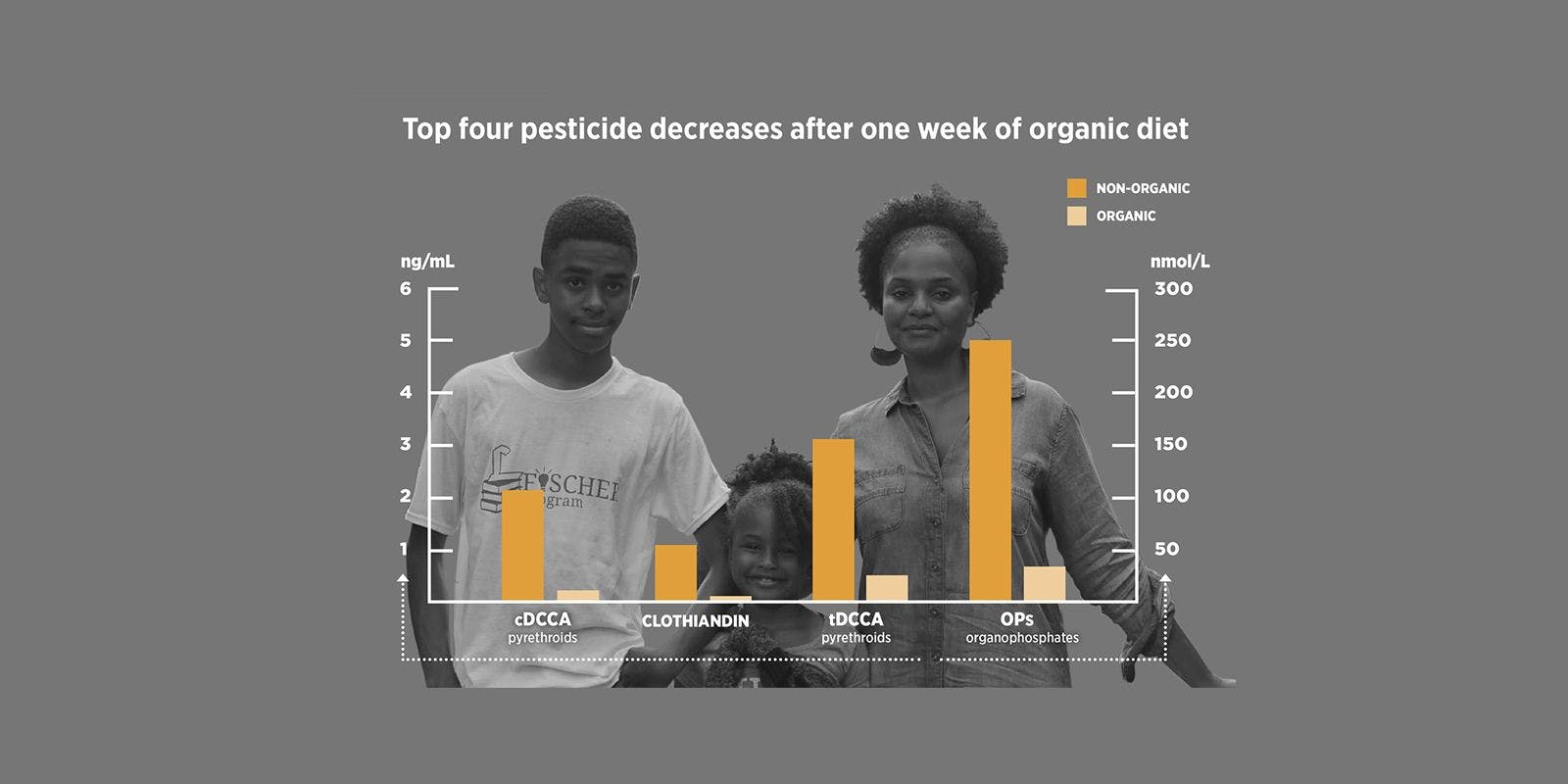

JF: Yes, that’s another part of it, is that we want to help people make the connection between what they eat and what it does to their body. So, for instance, we collaborated with Friends of the Earth, and they have actually an agricultural PhD on their staff, the head of their research program. And we collaborated with them to do a study where they identified six families that agreed to eat their regular diet for a week and give a urine sample every day, and then, at the end of that week, to switch to a purely organic diet and again give the urine samples. And then we measured the glyphosate levels in all of those samples.

And we show very clearly that, whereas the levels of glyphosate in the conventional diet were quite substantial, as soon as they shifted to an organic diet the levels began to go down, and within two days they were essentially free from glyphosate.

(11:09)

TM: You know, it’s so fun that you’re telling us that you did the lab work for that study, John, because just last month, after they released that, Dr. Kendra Klein was our guest, and she talked to us a lot about it.

Here’s a big question I bet a lot of people are asking, John, and that is, does it matter whether you have a lot of pesticides in your body? I guess the EPA doesn’t seem to think it matters, one. And then two, is there a way that you can test for glyphosate other than urine analysis?

JF: Oh, yeah. Well, that I can cover quickly. We also test here for glyphosate and its metabolites. And this is a longer record, because your hair grows about a little more than half an inch every month. And so if you then look at a strand of hair, it’s sort of like a record of your glyphosate consumption.

TM: Kind of like rings on a tree?

JF: Yeah, yeah, yeah, it’s like that, basically. And so we can have a longer-term record, which—it gives us a longer-term record than the urine test, which tells you what you ate in the last forty-eight hours, basically. And that also is interesting because if you ate that today and you were eating your normal diet, then it’s likely that you probably are pretty close to that same number on a regular basis. But the hair is another way of doing it.

TM: Many people here have said, well, you know, the EPA sets the regulation. And obviously the other thing in the question is at what age? We know that children in utero, infants, are much more vulnerable. But how are we—are we linking adequately, I should say, this contamination of our bodies with contaminants like pesticides and our health aspects?

JF: Yeah, yeah. Well, here is this health connection. If you look at the sort of government thresholds for what is allowed in commodities, you come up with massive levels of these things. And it is sort of implied that that indicates safety, but that’s not really an accurate assumption to make.

I’ll tell you here, I just pulled up a table that summarizes, it compares the U.S. EPA, the European Food Safety Authority, the California Prop. 65 authority. And what you see is that the amount of glyphosate allowed for safety—they say it’s safe to eat this much per day—and so for a 70 kilo, which is about like 150 pound person, it’s safe for them to eat 122 milligrams of glyphosate a day, according to the U.S. But according to the EU, you can eat 21 milligrams. That’s like six times less.

TM: That’s a big difference!

JF: It is. Now, the California Prop. 65 people say, well, actually, the highest you should go is 1.1 milligram per day. And I have gone to the California Prop. 65 website and looked at how they calculated that. Based on a complicated risk analysis prospect, they say that if you reduce your glyphosate to 1.1 milligrams per day, if the population did that, it would reduce the number of cancer deaths, or it would reduce cancer incidents by 1 in 100,000. Now, that’s not very big.

TM: Wow, yeah. What is it now?

JF: Well, for instance, glyphosate is known to cause non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. There are two legal cases that have been successfully fought on this topic in the last year or year and a half, and both of them gave multimillion-dollar settlements to people who had gotten non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma linked to use of glyphosate. So there are about 74,000 cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma per year in the U.S. Now, if you go through all the numbers, that would result in less—and if the whole country reduced their use by that much, to that level, you would see a reduction, almost an imperceptible change. It would be less than one fewer cases.

But if you reduce the level we consider—we’ve been thinking a lot about this, and we feel that instead of 1.1 milligram, the really safe place, where you take into account children and everything, would be more like 10 micrograms per day, much, much lower. And if you use the California Office of Environmental Health way of calculating it, going to that level would reduce the incidence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma by 50 percent. It would save more than 37,000 lives per year, which is pretty good. But you have to get low to do that.

Recently we have been testing a lot of organic foods, and what we find is that organically produced wheat, barley, spinach, apples, whatever you test that way, have less than that amount, or below that threshold for glyphosate.

(18:27)

TM: If you’re just joining us, you’re listening to Rootstock Radio, and I’m Theresa Marquez. And I’m here today with John Fagan, who is the CEO at the Health Research Institute Laboratories in Iowa, and he’s the executive director of the Earth Open Source Institute. We were just talking about how it looks like the statistics are looking like the less glyphosate you have and that you’re taking in your body, the less chance you have of getting a cancer such as non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

You know, I wanted to just talk a little bit about this Open Source. I’m wondering whether that’s still happening. I think it’s the Earth Open Source Institute who is actually doing open source testing of glyphosate. Are you still doing that?

JF: Yeah, but that actually is happening through Health Research Institute. We do what’s called Citizen Science Projects, where—the one that we’re working on now is a general broad screen of the population for glyphosate levels in urine. And we’ve been doing this for the last almost two years now, and so we have measured urine glyphosate for more than 2,000 people at this point. And this will get published in the next six months, probably.

And it basically comes with a questionnaire, and people will tell about their lifestyle, their diet, all of that sort of thing. And what we find is that there’s some things that were really surprising. We found that people who live in the country, maybe even right in an agricultural area, they don’t have higher levels of glyphosate than the people who live in cities, except for one exception, and that is the people who are the actual farmers who are using glyphosate in their fields, and they have higher levels. But the rest of the population, it appears that everybody gets it from the same place, which is their diet. And so if you want to protect yourself, you have to pay attention to your environment and your diet, basically, or your diet and secondarily the environment.

TM: So, for our listeners, HRILabs.org. That’s HIRLabs.org. And can the Citizen Science Project, can our listeners go onto your website and follow the directions and send in their lab sample?

JF: Yes, it would be great. We appreciate everybody doing this. Now, just to make sure people understand, one of the parts of citizen science is that every citizen, every participant, actually contributes in two ways. One is that they provide their sample and the information, but it actually costs money to do these tests. And so we ask people to pay for their test to be tested. And when you have, that breaks it down to a cost that is accessible to most people.

(22:18)

TM: You know, John, I really wanted to ask you another question about testing the nutrient value of food. You see so much information sometimes, especially demonizing organic: “Organic is not a bit healthier than conventional, and it’s definitely not more nutritious.” And even Stanford a few years ago came out with a study about how organic’s not as nutritious as conventional. And yet aren’t there many other studies that conflict with that? And have you found any evidence that shows the nutritional superiority of food that is produced organically without pesticides or without contaminants?

JF: Yes, those are really good questions. The situation is that, first of all, the Stanford people didn’t look at pesticides. They were just looking at a small number, a relatively small number of nutrients. So the big differentiator between organic and conventional, the first flat-out most important one is the presence of toxins or absence of toxins. And the difference between organic and conventional is massive. We see between 500- and 1,000-fold difference in glyphosate levels in conventionally grown oats and in organic. The differences are huge.

But putting that aside, you look at the nutrition, and there are a growing number of studies now that document the higher levels of healthy nutrients. For instance, the omega-3 triglycerides are a very important differentiator in milk. And I know, Theresa, you’ve spent a lifetime with organic milk, and there are big differences there.

TM: Well, relative to conventional, I call organic milk superfood, especially the Grassmilk.

JF: Absolutely. And that’s why the omega-3s are so differentiating. And then you also have a number of studies that have looked at vitamins and also at antioxidants and other bioflavonoids and these sorts of things, showing that there are significantly higher levels in organic than in conventional. So it isn’t as studied as some things in the scientific literature, but there’s a growing body of data documenting the higher nutritional value of organic, and certainly the safety of organic. So that’s really important.

And what we’re doing, we’re actually using this very powerful analytical technology to take the information, take the research to another, much higher level of rigor and comprehensiveness. Typically, with chemistry, you find what you’re looking for. If you don’t look for a certain compound, you don’t find it. You can’t find it—you can’t do it that way.

But the method that we’re using now is very open-ended. Mass spectroscopy [spectrometry?] can detect almost every molecule that nature has made or that human beings have made—almost every molecule. And therefore when you take a sample and you analyze it by mass spec, you’re going to see everything. And with the powerful methods that we have, we can actually resolve that into a clear picture of what is in that food and, from that, what’s the difference between that grass-fed milk and the CAFO milk. And that allows us to really give much more information. We’re not just trying to look for one thing, and maybe we find it, maybe we don’t. We’re asking a much broader question. We’re asking, well, what is there in organic milk, and how does that compare with what we see in the local conventional milk variety? And so it’s a much more powerful technology. And we’re just now getting to the point where we can begin to ask these questions in a very comprehensive way.

And milk is one of the things on our list that we’re really interested in looking at. I believe, when you’re feeding meat and bone meal to cows, it’s got to affect the milk; it’s got to affect the quality of that milk, and not in a good way. And that’s what’s happening in the conventional world.

TM: Right, not to mention just feeding corn and soy, which is high, high omega-6, which we all need but we just don’t need it in that much of a quantity as we do. And then the other thing about corn that I always like to keep bringing up and reminding people of: two bushels of soil goes down the Mississippi River here in the Midwest for every bushel of corn that we produce.

John, thank you so much for those wise words, and it’s been a real pleasure talking with you today. For our listeners, once again, HRILabs.org. And you can actually sign up and get your glyphosate tested, just to see where you stand in the scheme of things. And John, yes, thank you so much for your dedication and all this great work that you’re doing. It’s really an honor to have you and talk with you today.

JF: Oh, thank you very much, Theresa. I really enjoyed our conversation.

You can listen to Rootstock Radio on the go wherever you get your podcasts, and find us online at RootstockRadio.com. Rootstock Radio is brought to you by Organic Valley.

Thank you for being a part of our Rootstock Radio community!

Related Articles

- Tags:

- climate,

- pesticides & herbicides,

- environment,

- Rootstock Radio