Food

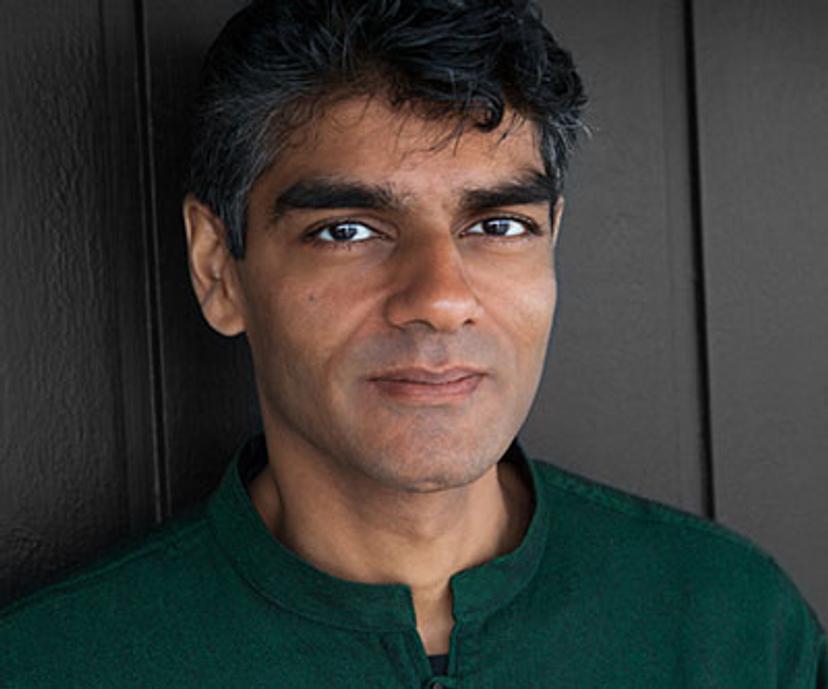

Rootstock Radio: Raj Patel: Capitalism is Catching Up to Us

Raj Patel, award-winning writer, academic, activist and co-author of the 2017 book A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things, says, “Cheap things can never stay cheap for long.” This truth—profound in its simplicity—has informed a lot of Raj’s recent research and writing. It’s something he talks about on the fortnightly food politics podcast The Secret Ingredient, which he co-hosts with Mother Jones’ Tom Philpott, and KUT’s Rebecca McInroy (Raj is no podcast novice—you’re in for a treat), and it’s something he explores with use today on Rootstock Radio, especially in how it relates to food and agriculture.

Tune in to hear about:

- What exactly these “Seven Cheap Things” are.

- Why food has historically been offered at lower and lower prices and why this approach is not at all sustainable.

- What Raj believes will happen if we continue operating in our current manner (Hint: it’s not good.)

- What Jeff Bezos and Christopher Columbus have in common (Yes, really!)

Listen at the link below, on iTunes, Stitcher, Google Play or wherever you get your podcasts.

Rootstock Radio Interview with Raj Patel

Welcome to Rootstock Radio. Join us as host Theresa Marquez talks to leaders from the Good Food movement about food, farming, and our global future. Rootstock Radio—propagating a healthy planet. Now, here’s host Theresa Marquez.

THERESA MARQUEZ: Hello, and welcome to Rootstock Radio. I’m Theresa Marquez, and I’m so honored to be here today with Raj Patel. Besides being an award-winning writer, he’s an activist; he’s an academic; he is a research professor in the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas in the most wonderful city of Austin; and he does a podcast with the infamous Tom Philpott from Mother Jones. And I also want to say that Raj’s books speak for themselves. I think you’ll all love these titles: Stuffed and Starved; The Value of Nothing. And then this newest one that we’ll probably talk a little bit more about today is The [A] History of the World in Seven Cheap Things. So welcome, Raj.

RAJ PATEL: Theresa, my goodness, what a fantastic introduction! I wish my mother had been able to hear that.

TM: (laughing) We’ll send you the podcast!

RP: (laughing) That would be lovely.

TM: I was so interested, of course, in your book. You know, the byline, “A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet.” Ah, we need this guide so badly. And it’s not just by Raj but it’s also by Jason W. Moore. But wonderful to be able to say “Seven Cheap Things.” And I thought perhaps we could start there and you could talk a little bit about what those seven things are. And when I saw the list, I went, “What’s cheap about them?” And I think that you’re going to be able to enlighten us.

RP: So the “cheap” things are nature, work, money, care, food, energy, lives. And the reason that they’re cheap is that we’ve got a story about how capitalism began. And capitalism began as basically a strategy that emerges out of the last big climate and disease crisis in Europe at the end of feudalism. And it becomes a strategy for the rich to be able to remain rich. And one of the ways that they do that is through colonialism. And one of the things that they have to do in order to stay rich is to make other people pay the price of their wealth.

And the story in the History of the World in Seven Cheap Things is the story of the origin, the dawn of modern capitalism and its arc, its sort of long history of trying to avoid paying its bills. And the trouble with cheap is that you can sort of kick the can down the road for a little while, but the cheap things can never stay cheap for long. In the end their costs always catch up with you. And so those cheap things, whether it’s about cheap work or cheap care or cheap lives or whatever it is, all of those seem to be coming to an end.

And we use a number of examples through the book to try and make concrete how not only does capitalism depend on seven things, but those seven cheap things—you know, the sort of constant search by capitalism for the next bargain, whatever that is—is now coming to an end. That we’re now in a period of such deep crisis that capitalism, as it has flourished over the past 600 years, cannot carry on as usual, and we’re about to move into something really dramatically different. And the argument we’re making in this book, in terms of the future of the planet, is that we would be wise to understand where capitalism came from, so that once it declines and collapses, we’ve got ideas around to be able to replace it with.

TM: Well, I love the idea that you’re thinking, you know, you can’t figure out where you’re going if you don’t know where you’ve been. And also, I love the idea that you’re trying to bring up a conversation or some messages that maybe some of us can use. Like, for example, since I got obsessed with the idea that capitalism is the problem, I’ve tried to bring it up a few times with my friends, and I’m having a really hard time discussing it. What kind of messaging are you developing that can really help us when we start to talk to our family and friends about why we’re concerned about capitalism? By the way, it’s the C word, you know—it’s like no one wants to talk about it.

RP: (laughing) Well, it’s true. I mean, I remember being at Berkeley, which one would think is a hotbed of lefties, but I once said “capitalism” at a food conference, and it was like I had farted in a lift. People were just a little perturbed that I would say the C word in public, and people were sort of a little awkward and ashamed.

And in part, that’s because capitalism has been so good at exterminating its alternatives that now most of us can rather imagine the end of the world than we can the end of capitalism. We’re much readier to believe that we will move full-throttle into the world of Mad Max than we might imagine other ways of distributing work and care and the resources that we need in order to survive.

And so, in a sense, Theresa, you’ve got a data point. When you’re finding that your friends and family don’t know how to begin a conversation about capitalism and get antsy with it, that’s actually something to embrace. That’s something to recognize and to say, “Well, actually, can you imagine any system other than capitalism?” And then people will say, “Oh, no, absolutely not.” And then we can point out the number of ways in which actually we give to one another generously and freely without wanting money in return, for things like care and love, for our engagement in community activities, in the ways that we interact with the rest of the web of life. Invariably, we don’t pay for some of the most deep and important parts of our lives, entirely free of capitalism. We experience them and we grow through them. And yet somehow those experiences don’t translate into, my goodness, what would it be like if all our relationships of work and of production and of creation were like the kinds of relationships we have when we care for one another.

So in a sense, that’s the argument that we’re making in the book, is that in order for us to understand what it is that we might look for in the future, we need to understand how successfully capitalism has gone out of its way to annihilate its competitors.

(7:26)

TM: So yeah, when you start talking about these seven cheap things—nature, money—say a little bit more about this 700-year history of how looking at these things and trying to make them the cheapest they can has got us to where we are.

RP: Well, let me do that in two ways. First of all, let me show you how these seven things work together. The example that we have in the book is the story of the chicken nugget, which we present as the most capitalist object ever. And that’s unusual because normally people think, oh, you know, it surely is the smartphone or a Porsche or… But actually chicken nuggets are really the sort of extreme example of capitalism. I mean, first of all, there are 12 billion chickens alive. We go through 50 billion of them a year. And as a result there will be trillions of these chicken bones strewn through the earth. If there’s ever any civilization after ours that comes and is able to dust the remains of our civilization away, they’ll find all these chicken bones. And those chicken bones don’t happen because of humans being humans. It’s capitalism at work.

I mean, here we are—here are the seven cheap things. So it’s an example of cheap nature because those chickens, the genetic material is taken from the jungles of Asia and now we have genetically engineered chickens where their breasts are so big they can’t even walk. But those chickens don’t turn themselves into nuggets by themselves. They need cheap labor. So you have workers that are paid very badly, and in the chicken industry some workers aren’t paid at all. And those workers’ bodies are broken on the very vicious production line. And so when workers suffering from far higher rates than everyone else of repetitive strain injury, for example, and injuries, are kicked off the line because they can’t work anymore, you need a community to take care of them. And that care work, usually done by women around the world, is another subsidy to capitalism.

But again, in order to care for people, we need cheap food in order for wages not to be too high and for care to happen. And in order for this cheap chicken to happen, you also need cheap fuel to heat up the hen houses and to transport the chicken. You need cheap money in order to be able to sell these nuggets at a subsidy—so cheap money really means money with low rates of interest. And every KFC in America is an example of something that’s subsidized to the hilt by the government and is able to get concessional low-interest loans so that we can have this cheap chicken. Of course, cheap lives is the story of how the people who are most likely to be working in the chicken industry are women and people of color.

And that story of how these seven things come together to make this chicken nugget is the story of how capitalism works. But it’s been set up that way for a long time. And the other example, other than the chicken nugget, we use is the story of Christopher Columbus, who touches all of these seven cheap things from the moment he gets to the New World. In fact, he apprentices in the sugar industry in Madeira off the coast of North Africa before he becomes Admiral Columbus. And Columbus is this sort of nasty figure who gives you an example of how it is that rapacious capitalism works today. And you know, his modern analog is someone like Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk, people who are able to parlay loans from financiers into colonization plans—in Bezos’s case, for the moon, and for Musk’s case, for Mars.

TM: You know, that’s so fascinating, comparing Christopher Columbus to Bezos. Maybe you could say a little bit about what are they doing that’s in common?

RP: Well, you know, I mean, Christopher Columbus famously paid his workers very badly on the Nina, Pinta, and Santa Maria. He offered a prize to the person who first saw land. One of his sailors in the middle of the night claimed to have seen land, and then Columbus wakes up and next day announces that no, no, Columbus had seen it first, despite having been unconscious at the time. And you know, that sort of moment of wage theft should be familiar. I mean, both Amazon and Tesla have had cases brought before the National Labor Relations Board for not treating their workers very well.

But Columbus also was famously a slaver. And no one is suggesting that Musk or Bezos are slavers, but their technology does depend on modern-day slavery. I mean, there are 40-plus million people in conditions of modern-day slavery, and among the things that modern-day slaves are involved in is the production and the mining of the kind of rare earth metals that find their way into a Tesla motor car or an Amazon Alexa. And so the reason that you’re able to order things in the shower from Alexa is because of the sort of layered exploitation of bankers and of software engineers and of janitors and of people in modern-day slavery, layered one on top of each other in ways which should be very familiar to people like Columbus.

And of course, the idea of colonialism offering a “new frontier” from which to exploit resources—that was Columbus’s bag, but it’s also something that’s, even as the book was going to press, you see a lot of it in things like the Financial Times. I got a copy of the Financial Times today with a “Space Mining” supplement in it. And there’s lots that Bezos wants to do on the moon to create this new ecology of capitalism on the moon. And when Musk talks about colonizing Mars, he’s not messing about. It is about creating these new frontiers where resources will be able to be exploited, and workers too, in order to be able to swell profits back up.

"Cheap things can never stay cheap for long."

- Raj Patel

(13:36)

TM: If you’re just joining us, you are listening to Rootstock Radio, and I am Theresa Marquez. And I’m here with Raj Patel, award-winning writer, activist, and academic. And we’re talking about capitalism and about how we might change the kind of pervasive greed that we have that seems to be driving everything. And also, Raj has a book, A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things, and it’s written with Jason Moore.

Well, you know, when you talk to people about capitalism, I think the first thing that comes into their mind is the American dream. Gee, I can be rich, I can be one of these people in the one percent. You know, that’s what capitalism is about: “free enterprise.”

RP: Well, I mean, I think George Carlin said it best when he said the reason they call it the American dream is because you’d have to be asleep to believe it. But nobody loves being told what to do. And I count myself firmly in that category, and I love free and uncoerced exchange. I think those things are terrific.

And starting from that point is, I think, an important place to then figure out where the disagreements lie, because in the terrific French historian Fernand Braudel, who points out that actually what modern capitalism is, is the anti-market. If you like free exchange and the sort of uncoerced “I’ll give you this in exchange for this much money—let’s haggle over it and then we’ll come to some decision”—that idea of free exchange where both parties are in some way giving and taking, that’s brilliant. But what capitalism does is concentrate power so much that the choices and the freedoms one has gradually diminish, and instead what we’re left with is its shallow alternative: consumer choice.

And the trouble with consumer choice is that then you’re reduced to choosing between Coke and Pepsi. And when you’re choosing between Coke and Pepsi, it’s true that they engineer it to be addictive, and the marketing is there to make us believe that we are engaging in singular acts of liberation when we drink it. The data is coming out all the time, including a study in the British Medical Journal today that suggests that, for example, if we’re looking at food, the more ultra-processed food we consume, the more likely we’re going to develop cancer. A 10 percent increase in the consumption of this kind of ultra-processed food leads to a more than 10 percent increase in rates of cancer. And if you want a free market, then surely, yes, you go right ahead and consume whatever you like but then pay for it in ways that are concomitant.

Or we could move towards recognizing that actually we probably do need to pay more for food, because the way that we have, you know, that the food is processed and consumed at the moment is precisely about making our children pay the cost and making the working class pay the cost and making nature pay the cost. And rather than engaging in this kind of chicanery, if you love free market, you have to pay the full cost. You can’t just cheat. And capitalism is precisely about cheating.

So I think starting where everyone agrees—that in fact uncoerced exchange is good—and then ask who is it that’s doing the coercing. In the end, I think one comes up with large corporations and the governments that they have fashioned in order to be able to execute their will. I mean, we like to believe that we live in a democracy, but I think increasingly the data is in that democratic isn’t the same thing as voting, insofar as we, the demos, the people, are making decisions that are reflected in our government. What the government is doing is a very minimal reflection of the popular will. One only has to look to attitudes about everything from gun control to immigration to corporate power to inequality, to recognize that our government is not the government of the people but the government of the 1 percent.

TM: You also have this idea that capitalism, it only could exist because of cheapness, but that it actually is failing, and that maybe there’s a transformation happening.

RP: Well, I think actually the history of the past 700 years isn’t the history of unfettered triumph for capitalism. Part of the reason that we have these seven cheap things is because, in one way or another, capitalism has never fully succeeded in coercing everyone. So the fact that workers are increasingly standing up for their rights, even in China—I mean, there are large-scale strikes every day in China. We don’t get to hear about them much, but there are workers who are in the “workshop of the world” demanding their rights and driving up the cost of work in China, making it less and less cheap. Although capitalists would rather have the world bent to their will, they have to bring everyone else along, and most people come kicking and screaming.

And so while the union movement is suffering blow after blow, it hasn’t gone away. While natural systems can be exploited, they cannot be exploited ad infinitum. And in fact, our relationship with the rest of the web of life and what we call “natural” is increasingly parlous and unstable.

And so the fact is that greed is learned, and it’s never learned fully. There’s a test that I wrote about in the last book I did, The Value of Nothing, which is what’s called a reciprocity game. And the idea of this game, you can play it at home. The game is that an experimenter comes in with a dollar in cents, and so you get 100 cents. And the experimenter will come to you, Theresa, and say, “Here is a hundred cents. You have to divide it between you and Raj. And then Raj gets to decide whether that division is okay or not. And if he agrees, then you keep what you’ve decided and he keeps whatever you’ve given him. But if Raj decides that it’s too unfair, then no one gets anything.”

And so, for a rational animal, for a purely greedy individual, what you would give me is 1 cent and you would keep 99. But almost every human says, you know, that’s absolutely wrong. Screw that, we’re not going to do it. But not every human is this greedy, rational being. In fact, it’s very unusual for humans to do that 99-1 cent split. You know, most people would give 50-50, 40-60, something like that. And it’s interesting, when this reciprocity game is played in different civilizations, some civilizations will give more than they keep, in order that next time the person you’re playing with owes you a favor. In what passes for western civilization, there is a category of people who are the most greedy. And the most greedy people that we know are graduate students in economics. They’re the ones who will keep the most for themselves and give the least to someone else.

Now, I think that that’s interesting, because it suggests both that the myths of greed are never as complete as we’re told. Even graduate students in economics, selfish bastards that they are, will still give 25 cents rather than 1, and that’s wrong of them, because if they were following scripture they would give only 1 cent. But they’re not rational animals, they’re not behaving as rational beasts. They’re behaving as people with some sense or semblance of “Oh, well, that doesn’t feel right.” And that kind of exchange suggests that, first of all, different civilizations continue to have different ideas about what’s fair, and also that we can learn to be less greedy.

And I think that’s important, because often when we think of capitalism, it is a story of unfettered greed and the triumph of the 1 percent over everyone else. And it’s never been a triumph, it’s never been automatic—it’s always been fought back. That’s why unions and groups of indigenous people, and people of color, and the women’s movement, all of these signs are examples of moments when capitalism tries to get something for free and it can’t get away with it, and people organize and fight back. And I think that’s something that’s important to recognize, particularly today: that there’s nothing inevitable about capitalism’s rise, and even though there may be something inevitable about its collapse, the contours of that collapse are entirely up to us.

TM: When you say it’s entirely up to us, you almost sound like we actually have a choice, when one of the hardest challenges we have is actually working together and cooperating. There seems to be a conflict, I think, between this idea of democracy—and I’m so happy that you brought that up—and greed, and our inability to kind of work with each other and cooperate. Marcus Aurelius said we are born to cooperate, and we would never have gotten here if we didn’t. How do we bring more of that back in, so that we actually do have a choice of trying to do a little bit more, what I think you call systematic change is needed.

RP: I mean, I think that actually Marcus Aurelius is right. And in fact, everything we know about humans is that we are a cooperative species. There’s no story of a human born alone, lives in the words, and survives happily. Humans need one another—we need one another. We’re a social primate. So the question is, how do we engage that side of ourselves much more than we have recently?

And partly, I think, the kind of sorry state of politics in the United States and elsewhere has much to do with the way in which we spend much of our time on our phones, in our own little bubbles. And that’s not terribly good for cooperating because one doesn’t learn how actually to do anything with one another. But also, I think it is possible for us to have our minds changed, for us to engage with people who are very unlike us and to build together.

And I, quite by accident, was exposed to some of this because I do work in sub-Saharan Africa with an incredible group called the Soils, Food and Healthy Communities project. And some of the farmers and activists there were concerned about climate change, and they wanted to come to America to talk to folk here about climate change. And so over the summer I was able to see what it’s like for folks to cooperate and communicate across some very seemingly unbridgeable divides. But precisely because folk could set aside sort of the contrived ideas about politics that normally we read each other with, and rather just sort of sit with these two amazing women from Malawi and have a decent discussion, it was possible to move beyond the kinds of impasse that we find in our political system and actually start a conversation about, well, how might we work together?

And that idea, it seems to me, that reality is something that you’ll be able to see in theaters near you next year, but it gives me hope. I mean, it’s the sort of idea where actually it is possible for us to be able to transcend these partisan divides. But in order to do that, we do need to sort of spend much less time on social media, turn our phones off, turn our TVs off, and convene around a table. It’s much harder to have decent conversations online than it is when we’re looking into each other’s eyes, being embodied people, and ready and open to have our minds changed.

(25:03)

TM: I want to go back to those seven cheap things for just a second. If we look at nature and energy, which are not going to be cheap anymore—water, let’s just talk about water. Those things are going to get more and more expensive, whether we like it or not. And so if one or two of those—nature, you know, money, work, care—changes, could it upset the whole way that we’re looking at capitalism, do you think? Could it lead to this transformation that we both want so badly?

RP: Jason and I wrote the book, not because we’re necessarily excited about what comes after capitalism. There’s no guarantee that what follows is going to be better than what we have now. So in India, for instance, the prime minister is what most people would term a fascist. It’s not a pleasant place to be. In terms of environmental change, water is running out. In terms of climate change, he’s someone who’s very pro-coal. In terms of social justice, he’s someone who sees Islamophobia and Islamic terror around the corner. He bullies the country from his social media account, and he is a scourge on justice and on gender equality. This should all seem very familiar.

But the outcome of a country in crisis like India is not necessarily to move toward social justice but actually to move towards fascism. The trouble is that as we move towards a time of combination of climate crisis and things like the price of food going up—whether you like it or not, even if you exploit workers, the fact is that we know the price of food is going to be going up over the next few years and in perpetuity because of climate change. So I don’t think that capitalism can survive with the end of many of the things that it takes for granted and has taken for granted through a few hundred years of fairly stable climate.

And so what comes next is either more exploitation of human beings and sort of hollowing out of nature entirely, or a transformation. And I very much want that transformation to happen in a way that sets as many people free as possible from the chains in which we find ourselves. But there’s no guarantee, and we’re both good enough historians to know that what comes next may not be better. But I do think that insofar as we can look at first nation communities and indigenous communities that have figured out ways of thriving despite colonization and despite the severe damage that’s being already inflicted on the planet and the web of life, I think that we can derive inspiration from those communities and their ways of living, so that we can arm ourselves better to be able to socially organize for what comes after the various crises that will come through capitalism.

TM: Raj, it’s been such a pleasure to be speaking with you. If our listeners want to maybe listen, or are you doing a webcast or any videos?

RP: If you go to TheSecretIngredient.org you’ll find it there. And the work, the film work that I’ve been doing, which I’m very excited to share maybe next time, is done with the director of Hoop Dreams, and we’ve been working on that for seven years. It’ll be out next year. And if you go to GenerationFoodProject.org you’ll find it there.

TM: Raj, thank you so much for being who you are and doing what you do. I really appreciate it.

RP: Thank you so much. It’s a real honor to talk to you again.

You can listen to Rootstock Radio on the go wherever you get your podcasts, and find us online at RootstockRadio.com. Rootstock Radio is brought to you by Organic Valley.

- Tags:

- innovation