Rooted

Decoding the Farm Bill: Its Impact on Ag, Food and Rural America

The farm bill is a comprehensive piece of legislation that plays a critical role in shaping our food system. In fact, the farm bill is so important that it affects everything from the price and availability of food to the quality and safety of the products we consume.

From crop insurance to healthy food access, from beginning farmer training to support for sustainable farming practices, the farm bill sets the stage for much of our food and farm system. Every five years, the farm bill expires and is updated through an extensive process in which legislation is proposed, debated and passed by Congress and then signed into law by the president.

The farm bill concerns all of us as food consumers. The food we eat originates from the land, and thus the state of the agri-food system truly impacts us at every meal we eat and every trip we make to a farmers market or grocery store. It has important implications for human health, community well-being and equity in the United States.

The farm bill provides funding for programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which helps low-income families purchase food. It supports conservation efforts, which help protect natural resources like water and soil and ensure the long-term sustainability of our food supply while addressing the ever-growing complexities of climate change.

The farm bill sets policies related to agricultural commodities, subsidies and credit, all of which significantly impact the types of crops that farmers grow and the price of those crops. The bill also has major implications for addressing the long-standing structural and institutional racism that has historically excluded Black, Indigenous and people of color from accessing land, financial resources, political standing, educational and professional opportunities, and information.

The current farm bill, the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, is set to expire in September, and the process of creating a new bill is underway. So now is an important time for everyone to understand the farm bill and its implications for our food system and for creating a just society. Quite literally, the farm bill connects the food on our plates, the farmers, ranchers and farmworkers who produce that food, and the natural resources that make growing food possible now and in the future.

The following materials provide a comprehensive overview of what the farm bill is, offer historical context and present recommendations for how the next farm bill can build resilience and equity, restore competition, invest in science and regenerate our environment for current and future generations.

These resources have been created and drafted by the skilled policy analysts and advocates at the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC) in collaboration with NSAC’s grassroots members and with insightful input from the farmers and ranchers they serve.

Franklin D. Roosevelt gives a campaign speech to farmers in Topeka, Kansas, on Sept. 14, 1932, promising them a “new deal.”

The History of the Farm Bill

The original farm bill(s) were enacted in three stages during the 1930s as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation. Its three original goals — to keep food prices fair for farmers and consumers, ensure an adequate food supply and protect and sustain the country’s vital natural resources — responded to the economic and environmental crises of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. While the farm bill has changed in the last 70 years, its primary goals are the same.

Our food and farming system confronts new challenges today, but through citizen and stakeholder action for a fair farm bill, we can ensure the vibrancy and productivity of our agriculture, economy and communities for generations to come.

Introduction to the Farm Bill

The farm bill’s chapters are called titles. The number and substance matter of the titles can change over time. The 2018 farm bill, for instance, has 12 titles.

Here’s what they’re called (and what they cover):

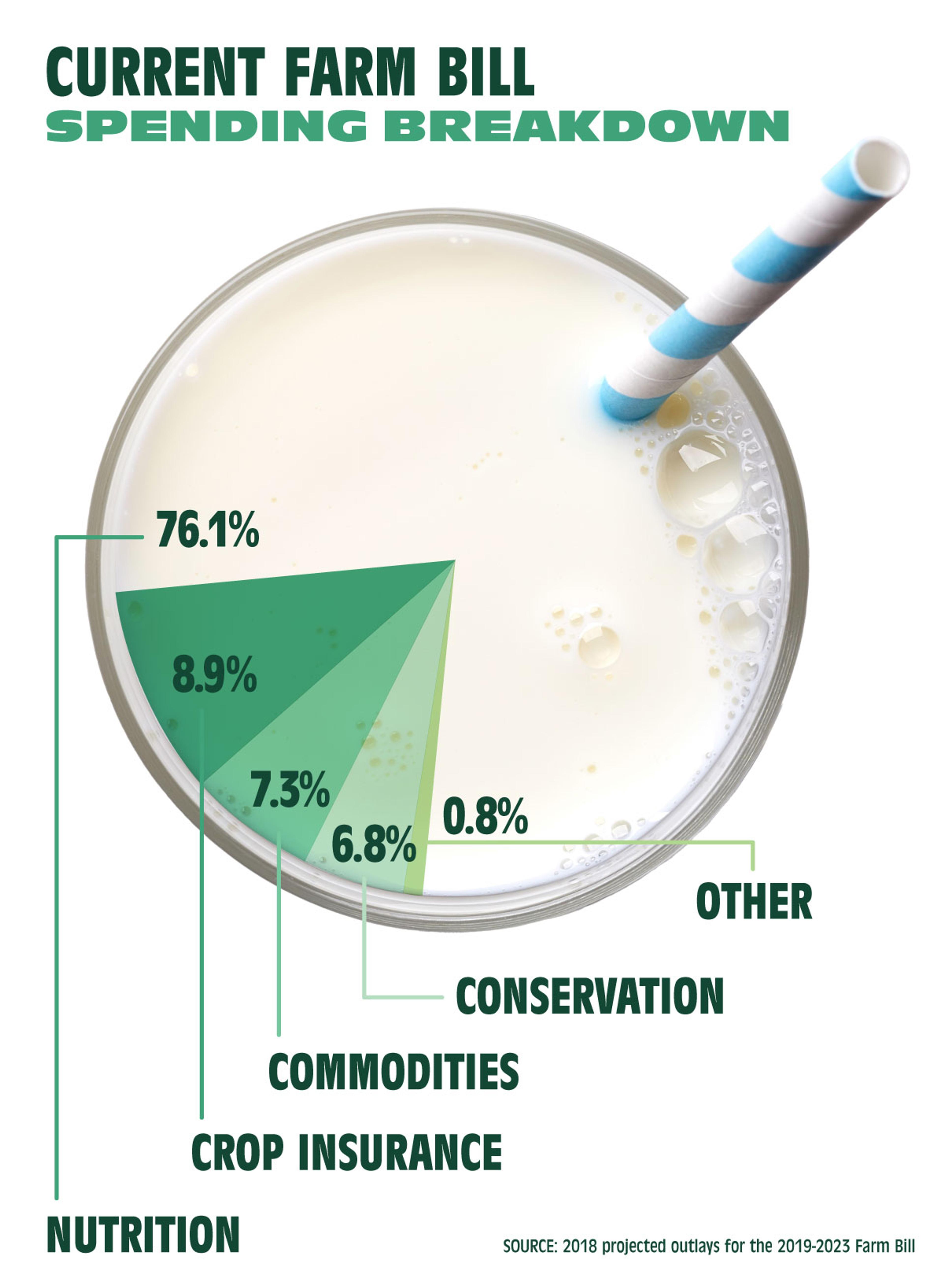

Commodities: The Commodities title covers price and income support for the farmers who raise widely produced and traded nonperishable crops like corn, soybeans, wheat and rice — as well as dairy and sugar. The title also includes agricultural disaster assistance.

Conservation: The Conservation title covers programs that help farmers implement natural resource conservation efforts on working lands like pasture and cropland, as well as land retirement and easement programs.

Trade: The Trade title covers food export subsidy programs and international food aid programs.

Nutrition: The Nutrition title covers the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (formerly known as food stamps) and a variety of smaller nutrition programs to help low-income Americans afford food for their families.

Credit: The Credit title covers federal loan programs designed to help farmers access the financial credit (via direct loans, as well as loan guarantees and other tools) they need to grow and sustain their farming operations.

Rural Development: The Rural Development title covers programs that help foster rural economic growth through rural business and community development (including farm businesses) as well as rural housing and infrastructure.

Research, Extension and Related Matters: The Research title covers farm and food research, education and extension programs designed to support innovation, from federal labs and state university-affiliated research to vital training for the next generation of farmers and ranchers.

Forestry: The Forestry title covers forest-specific conservation programs that help farmers and rural communities to be stewards of forest resources.

Energy: The Energy title covers programs that encourage growing and processing crops for biofuel, help farmers, ranchers and business owners install renewable energy systems, and support research related to energy.

Horticulture: The Horticulture title covers farmers market and local food programs, funding for research and infrastructure for fruits, vegetables and other horticultural crops and organic farming and certification programs.

Crop Insurance: The Crop Insurance title provides premium subsidies to farmers and subsidies to the private crop insurance companies that provide federal crop insurance to farmers to protect against losses in yield, crop revenue or whole farm revenue. The title also provides USDA’s Risk Management Agency (RMA) with the authority to research, develop and modify insurance policies.

Miscellaneous: The Miscellaneous title is a bit of a catchall. The current title brings together six advocacy and outreach areas, including beginning, socially disadvantaged, and veteran farmers and ranchers, agricultural labor safety and workforce development, and livestock health.

Livestock health is covered in the farm bill. Shown are cows on the Gearing farm in Wisconsin.

Who Writes the Farm Bill?

Members of Congress who sit on the Senate and House Committees on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry hold the primary responsibility of drafting farm bills.

What Is Not Included in the Farm Bill?

While the farm bill covers a swath of key agricultural policy topics, there are policy areas that are not included, such as:

- Farm and food worker rights and protections.

- Public land grazing rights.

- Irrigation water rights.

- Food and Drug Administration food safety.

- Renewable fuels standards.

- Tax issues.

- School meals.

- Women, Infants and Children (WIC) program.

- Some pesticide laws.

- Clean Water Act.

- Clean Air Act.

While these issues are directly related to agriculture, they are not included in the farm bill because they fall outside the jurisdiction of the Agriculture Committees and are instead considered under the jurisdiction of other committees. For example, farmworker rights and protections fall under the jurisdiction of the House Education and Labor Committee and Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee.

How Does the Farm Bill Process Work?

There are four main phases of the farm bill process, from drafting the new legislation to putting the programs into effect on the ground. Here’s how it works:

Step 1: Reauthorization

In the Reauthorization phase, a new farm bill is written and passed into law approximately every five years.

Hearings: Legislatively, it all begins with hearings (in Washington, D.C., and across the country). These are listening sessions where Congress members take input from the public about what they want to see in a new bill.

Agricultural Committees

House and Senate Agriculture committees each draft, debate, “mark up” (amend and change) and eventually pass a bill; the two committees work on separate bills that can have substantial differences.

Full Congress / ‘The Floor’

Each committee bill goes next to “the floor” — the full House of Representatives or Senate. Each bill is debated, amended and voted on again by its respective body (House or Senate).

Conference Committee

After both the full House and Senate have passed a farm bill — which can take a while, and may require a bill being sent back to committee for more work before passage! — the two bills (House and Senate) go to a smaller group of senators and representatives called a “conference committee,” which combines the two separate bills into one compromise package. Conferees are typically chosen mostly from among House and Senate Agriculture Committee members.

Full Congress / ‘The Floor’

The combined version of the conference committee’s farm bill then goes back to the House and Senate floors to be debated — and potentially passed.

Last Step: The White House

Once the House and Senate approve a final farm bill, the bill goes to the president, who can veto it (and send it back to Congress) or sign it into law!

The U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C.

Step 2: Appropriations

Once the farm bill is signed into law, it’s time for the appropriations phase: setting money aside in the yearly federal budget to fund the programs in the farm bill. Rather than a calendar year, the federal government operates on a fiscal year from Oct. 1 to Sept. 30.

Some farm bill programs — called entitlements — are written in such a way that their funding is guaranteed with “mandatory money” that will automatically support the program every year. An example of an entitlement program is the Supplemental Nutrition Access Program (SNAP). Other programs are authorized but funded through discretionary spending — meaning agriculture appropriators must decide each year how much funding (if any) to award a program. Because of budgetary constraints, not every program can be structured as an entitlement and generally it is much easier to include new programs in the farm bill if they are subject to appropriations.

Though the farm bill expires and is reauthorized every five years or so, the appropriations process takes place each year. The farm bill includes language that authorizes programs and sets the maximum funding levels for each program for the years covered by the farm bill. However, authorized funding isn’t the same as appropriated funding and appropriators may choose to provide funding well below the maximum amount that was authorized. The Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) program, for example, has been authorized at $60 million per year since it was first introduced in 1985, but has not yet been funded above $37 million per year.

The Placke farm in Wisconsin.

1. First, the president’s budget proposing how funding should be allocated to various federal programs is sent to Congress for its consideration. The House and Senate budget committees then draft and negotiate a concurrent budget resolution. The concurrent budget resolution provides appropriations committees with a framework for making funding decisions and sets a ceiling on how much funding is available to the appropriations committees for determining which programs receive discretionary funding.

2. Next, the process moves to the House and Senate appropriations committees, responsible for determining program-by-program funding levels across all areas of the U.S. government. Oftentimes, appropriators use the president’s budget as a starting point for negotiations and decisions. Very rarely do they simply accept the president’s recommendations.

3. Within the House and Senate appropriations committees are agricultural appropriations subcommittees — the people responsible for designating farm, food and rural development program funding. The subcommittees get input for their funding decisions in a few ways:

- By holding public hearings and inviting testimony from experts and agencies.

- By requesting and considering funding requests from all legislators and staff (both on and off committee).

- By meeting with constituents and advocates of programs to discuss funding priorities.

4. From this input, the subcommittee staff puts together a proposed agriculture appropriations bill that the subcommittee will review and make changes (aka amendments) to, and approve the bill through a process called “markup”. Once passed by the subcommittee, these bills are submitted to the full appropriations committees, where they go through another round of review and changes — “full committee markup.”

5. Once a bill has been marked up by the full Appropriations Committee, following subcommittee markup, the bill is brought to the full floor of the respective chamber of Congress for consideration. During the full floor passage, members of Congress can also make further changes to the bill, via amendments, prior to final passage.

6. Much like with the farm bill, differences in House and Senate appropriations bills get sorted out via a small group of legislators called the Conference Committee. Legislators have until the end of the fiscal year (11:59 p.m. Sept. 30) to reconcile their chambers’ respective bills, write a single compromise bill and pass it on the full floor of both the House and the Senate.

After Congressional passage, the bill is sent to the White House and signed into law by the president. Because the appropriations process is such a contentious process, this deadline is not often met, and lawmakers must then pass a “continuing resolution,” which maintains existing funding levels from the previous fiscal year so as to prevent a government shutdown.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture building is in Washington, D.C. The USDA was established in 1862.

Step 3: Rulemaking

Happening concurrently with the annual appropriations process is rulemaking. After Congress passes a farm bill, the U.S. Department of Agriculture is responsible for writing the actual rules for how these programs will be implemented on the ground. This phase is called Administration (or Rulemaking).

Wins for sustainable agriculture in the farm bill require vigilant attention during this phase to ensure the rules implement programs in a way that reflects the intent of Congress — and of the farmers and advocates who helped shape the bill!

- Advocates and experts check in with agency staff at USDA, track the status of particular programs and share their input.

- Grassroots individuals have a major role to play during this stage, by commenting on USDA’s proposed rules for farm bill programs.

- Proposed agency rules are published in the Federal Register and are usually open for public comment from 30 to 90 days.

Step 4: Outreach and Evaluation

And always, when program funding is appropriated and rules are set in place for implementation, it’s time for outreach and evaluation!

Here is the true test of program success: Do farmers, ranchers and grassroots organizations use the program? Does the program accomplish its goals and reach the people it is meant to reach on the ground? Is it having an impact?

At this phase, grassroots organizations and USDA both promote funding opportunities, requests for grant proposals and sign-ups for programs. Spreading the word is important to make sure everyone hears about programs and can access the information needed to participate.

And following up on the successes and challenges of specific farm bill programs is another key step in improving our food and farming system. By sharing evaluation and feedback on farm bill programs, farmers and constituents give lawmakers and agencies the information they need to fix any problems in the bill, and to work toward building a better farm bill for everyone.

Related Articles

- Tags:

- food & farming policy,

- organic news